by Joseph Bruchac

The following blog post was written by my father Joseph Bruchac and posted here with permission from his new blog GENERATIONS.

Ndakinna means “Our Land.” That is one of the words for home-ground among the western Abenaki people who are among my ancestors on my mother’s side of the family. (As I have mentioned earlier, half of my heritage is Slovak, a grandmother and grandfather who found themselves forced to leave their homeland forever to seek a new, freer land.) That concept of home-ground, of the land being home in the widest sense of the word, is one of the things I love about the Indigenous parts of my heritage. It is a sense of the earth itself, the whole land, not just the confines between walls and roof. It has shaped my way of seeing and walking. It has also led to my living, today, in the same house where I was raised by my grandparents. And that house, in the Adirondack foothills town of Greenfield Center, was built on the foundation of an older house owned by my great-grandparents before it was burned. When you ask a person about themself, they will often begin by talking about their family. That is because our families make us who we are. I want to go one step further than that. To talk about myself, about my concept of home-ground, I must talk about that land which shaped my Native ancestors, that land which made them and continues to make us.

There is an old, old story told by the Abenaki people. In that story the Creator has finished making the earth. I have shared a version of this story on my blog already, The Coming of Gluskonba.

They say that dust of creation remained on the Creator’s hands. So, Ktsi Niwaskw, the “Great Mystery,” brushed off that dust. It fell to the earth and the earth began to shape itself. It shaped itself into a body and arms and hands and a head. Then that dust, that earth which shaped itself, sat up.

“Awani kia,” says the Creator. “Who are you?”

“Odzihozo nia,” that one answers. “I Am the One Who Shaped Himself.

Then Odzihozo began to drag himself about on the land, for he had not yet shaped legs. With his body he created mountains and lakes and the beds of rivers. The earth around us, here, in New England, made that first one and was shaped by that first one. In the late 1980s I told that story in a courtroom in Vermont. I told it on behalf of the Abenaki, for the trial was a trial focusing on fishing rights. To assert their ancient aboriginal rights, a large number of Abenaki people had deliberately fished without licenses and then insisted upon being tried in a court of law.

At the time, the Abenaki were an unrecognized Native American tribal nation in the United States. We were here and we had been here, yet for a century we had been an almost invisible presence. Until recently, the official histories of Vermont said that “there never were any Indians living in Vermont.” If we lived there now, it wasn’t really our home. Either that or we weren’t really Indians. In fact, Indians had learned early on to keep a low profile if they wished to go on living in Ndakinna. It became so dangerous in the 1800s to be an Indian in the east that the western Abenaki people began to hide, as we put it, “in plain sight.” We dressed and acted much like those around us, but there were always those of us who kept our stories, our traditions, our language and our understanding that this land is our home. My telling of that story was an assertion of our long relationship to the land, a relationship which goes back to the time when our land was shaped by the glaciers. I told other stories that day, stories which talk about Ndakinna.

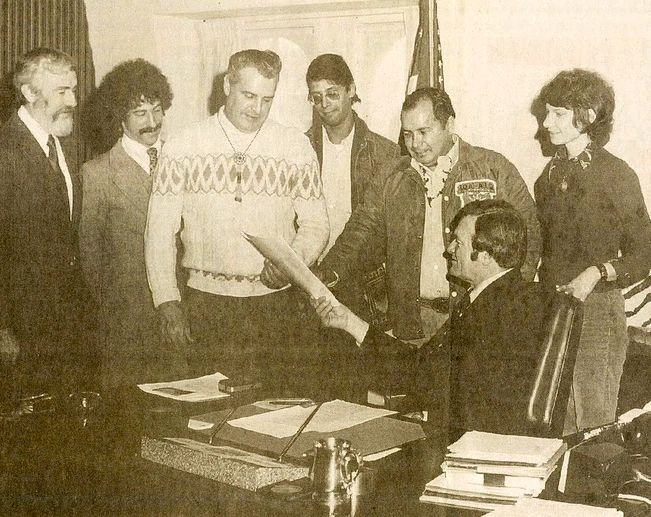

In the 1970s and 80s, Chief Homer St. Francis, of the St. Francis Sokoki Band of the Abenaki at Missisquoi, held “fish-ins” on the Missisquoi River. He and other Abenaki people declared exemption from fishing fees and invited Fish and Game officials to arrest them. My testimony was only a small part of the evidence which was offered, evidence given by people who had never forgotten their ties to a land which had sustained their ancestors and shaped their own lives to this day. The result of that trial was a victory for the Abenaki people. In 1989, the Vermont District Court ruled in favor of the Abenaki right to fish for free, but like Gov. Salmon’s executive order granting official recognition in 1976, the decision was overturned, this time by the Vermont Supreme Court, in 1992, saying the “weight of history” made our claims no longer legal.

Yet their history was a history of less than two centuries. Ours goes back ten thousand years. What seems old to modern-day Americans is newer than yesterday to those who live with a long memory of the land. Memories of home are the last memories to be forgotten. In 2020, the Vermont Legislature voted to restore free fishing and hunting rights to the Abenaki. H.716 provides free fishing and hunting licenses to anyone who is “a certified citizen of a Native American Indian tribe that has been recognized by the State.” There are now four officially recognized Abenaki tribes in the State of Vermont, including the Nulhegan Band of the Coosuk Abenaki Nation (2011), Elnu Abenaki Tribe (2011), Koasek Abenaki Tribe (2012), and the Missisquoi Abenaki Tribe (2012).

There has been a long misunderstanding between the Native peoples of this land and those who came later, especially those who came from Europe, where land had become property, where “land speculation” and “land development” would effectively replace older European ideas of land as mother, land as sustainer, land as sacred. That view of land has produced an American culture which is both rootless and ruthless in relation to the earth. The idea of the frontier, of always moving on to a newer and better place, produced a culture of waste. Gold mining, which physically destroys the land (and is currently poisoning and tearing the lungs out of the Amazon rain forest of South America), is the most extreme example. That search for gold produced such by-products as the dispossession of the Cherokee Nation and the wholesale killing of the Indians of California by the Forty-Niners. The early pioneer heroes of that culture, people such as Daniel Boone, were, in fact, real estate speculators. When you look at the American landscape as a mother, as a home to be cherished, then the history of the “settlement of America” is an unmitigated tragedy.

To Native people, the land, this home-ground which sustains us, is alive. More than once, Native people answered Europeans seeking to buy their land with words like these spoken by Hinmaton Yalatkit (“Rolling Thunder in the Mountains”), the man best known to history as Chief Joseph: “The Earth and myself are of one mind.” Then they would ask, “How can I sell my Mother?”

This vision of the wider earth as home was based not only in philosophy and in traditional stories, but also in the lifestyles of many Native peoples. Instead of having a village where one lived twelve months of the year, as would the new settlers of New England, there was a seasonal pattern of movement and migration. The winter village might be in one place, dependent upon food sources. The summer village would be in another. Several different sites might be used throughout the year, with no one place being the only permanent home, but all of those places being home-ground. Even the hunting territories were used in a cyclical fashion. This led some to describe Native people as nomadic, with the implication that they were “people of no fixed abode,” and “homeless wanderers.” The truth is that ours was a circle of habitation, a home in many places.

There are two stories of homecoming that I want to share. The first is my own. After being raised in that house in Greenfield Center by my maternal grandparents I went off to college. My grandmother had died when I was sixteen, but my grandfather, Jesse Bowman, remained there. He was waiting for me to return. He continued to run the little general store and gas station, which he had built next to the old house. He seldom made any money, for he trusted everyone and allowed them to write what they owed him in his account book. I think that trust, like his philosophy of gentle child rearing which had been given him by his own parents, was one of the legacies of his Indigenous ancestry. In the old days, among our people, a man was only as good as his word. If you promised to do something, you would do it. It didn’t matter if there were no witnesses and no written papers. The land could hear you, and the land would remember. And my grandfather always looked at the land with respect.

I think my grandfather made such a promise to the land. He would wait there for me, keep our home until I could return home. When I married and then went on to graduate school he was still waiting, now keeping that home-ground for me and my new wife, Carol. When Carol and I volunteered to teach in West Africa for three years and then had our first son, Jim, my grandfather still held on to that promise he had made to himself and to the land. He kept our home for us to come back to.

Those were hard times in America. It was the end of the 1960s, a time of rebellion and uncertainty, the assassination of leaders, the start of a loss of innocence, the hard time of the Vietnam War. I was not sure we would ever return to the United States when we left for Ghana in 1966. Yet my grandfather’s faith and the love of the land did call me back home. In the fall of 1969 we returned to Greenfield Center, moved into the old house and stayed. Late that winter, my grandfather passed on. Our family doctor told me that my grandfather had so many things wrong with him, from lung cancer to pernicious anemia, that it was a wonder he had managed to hang on as long as he did.

“He could have died four years ago,” Doc Magovern said, “but he was bound and determined to see you come home.”

And so he did. Though his body has gone back to the dust of our land, his spirit is alive. And his presence is always here with me in the house that has been our family home for five generations, in the gardens he planted that I now plant, in the stream where he helped me catch my first fish, in the paths through the woods we first walked together picking berries when I was barely able to stand on my own. He still reminds me that this place is my home, that caring for it is my responsibility, that we will always be part of the land.

The second story is one that I thought I would not live to tell, for it is a story of another larger return, a homecoming that was prophesied two hundred years ago. After the American Revolution, the Mohawk people were dispossessed of their homeland in the Mohawk Valley of New York State. They found themselves forced to move north. Two of their communities found themselves on small tracts of land along the St. Lawrence River — the St. Regis Reservation which is half in Canada and partly in the United States and Kahnawake, the “Rapids Place,” a village name which had once been given to lands along the Mohawk River in New York State.

To the west of the city of Amsterdam, there along the Mohawk River, there is an ancient village site. Archaeologists have found, there, the remains of not one or two but many different villages from long ago, each one built on top of the remains of an older one which was left behind in that ancient pattern of moving the village — villages where my Mohawk ancestors from grampa Jesse’s side of the family once lived long ago. That site has been known as Kanatsiohareke, the “Place of the Clean Pot.” The nearby village of Canajoharie is simply a misspelling of that Mohawk name. On that village site of Kanatsiohareke the county ran a farm for the impoverished elderly.

There was a prophecy spoken in the early days of the Mohawk removal. One day we will return to our homeland. It seemed a distant dream. Edmund Wilson’s nonfiction book Apologies to the Iroquois was published in 1960. Part of that book tells how one Mohawk visionary, a man named Standing Arrow, tried to make that prophecy come true in the late 1950s, camping with a small band of followers on land along Schoharie Creek. Eventually their occupation failed, though similar attempts at reclaiming Indian homeland would continue to take place in New York and other parts of the country over the next three decades – from Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay to Yellow Thunder Camp in the Black Hills of South Dakota. Such attempts are still taking place. There is a very long memory of home in the hearts of the Native peoples of North America.

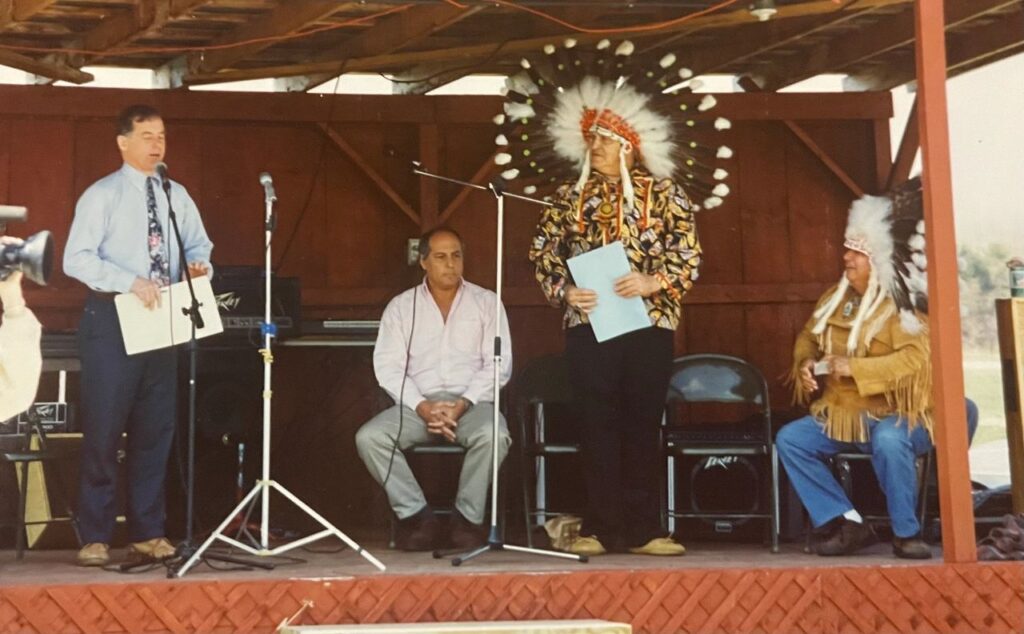

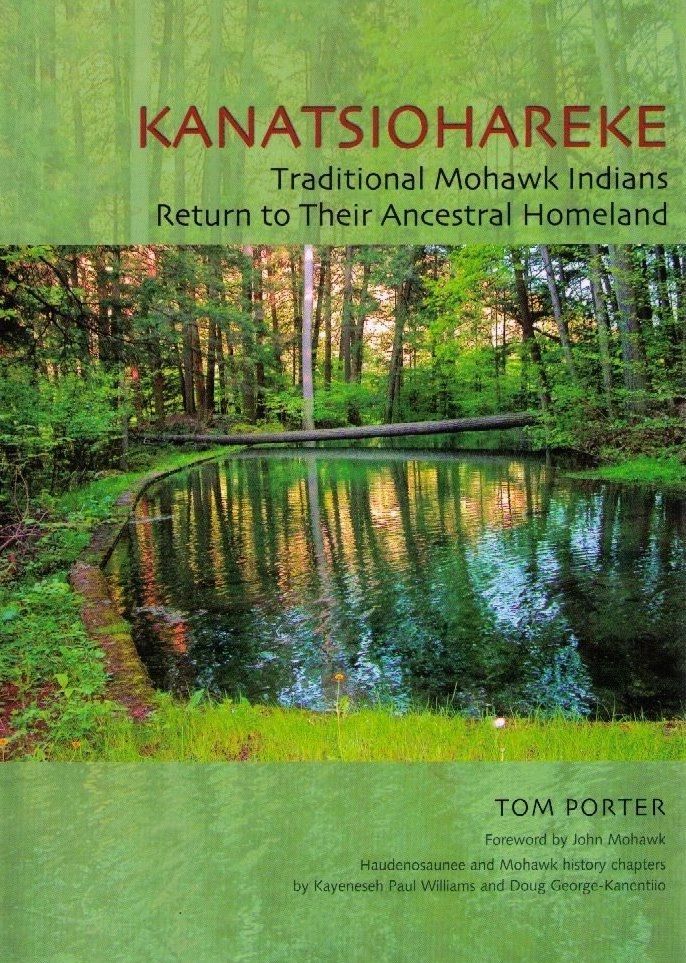

Three decades ago, another group of Mohawk people, led by Tom Porter, a nephew of that same Standing Arrow, began to raise money to purchase land in the Mohawk Valley. Their aim was to start a community which would honor their old homeland, a place where the Mohawk language would be spoken, a place free of gambling and violence, of drugs and alcoholism. It seemed like a dream until an unexpected donation was given to them, and their bid was accepted at an auction which sold off that five hundred acres which had once been a county farm. In 1993 Kanatsiohareke was born again. The village had come home. There, along the Mohawk River, a kind of healing had begun. We had the great honor to publish a book about the community, Kanatsiohareke: Traditional Mohawk Indians Return to Their Ancestral Homeland, under our Greenfield Review imprint Bowman Books in 2006.

When we are at home in the natural world, we are whole. We are whole not just physically, but also in mind and in spirit. It is a wholeness which preserves and sustains. It is neither romantic nor otherworldly. It is deeply, urgently practical.

The ecological sense of the Native view of land as home is evident. Native people understood that we must treat our homes with respect. Just as a modern person, today, would not be likely to set fire to his or her own carpet or break one’s own windows, so, too, in the old days would it be regarded as strange for a person to seek to kill all the game animals, to cut down all the trees, to make the water so dirty that the fish would die and the water would be unfit to drink. One might move, but one did not move on. It was understood that no matter where we went during our lives, we did not leave the earth behind. It is an understanding that is desperately needed today if we wish, as Americans, as human beings, to find our way back home again. It is an understanding not only for this generation, but for the generations to come.

To read more daily blog posts by Joseph Bruchac visit his GENERATIONS BLOG