by Joseph Bruchac

The following blog post was written by my father Joseph Bruchac and posted here with permission from his new blog GENERATIONS.

Saratoga’s Unspoken Heritage: A Journey into Hidden Native History

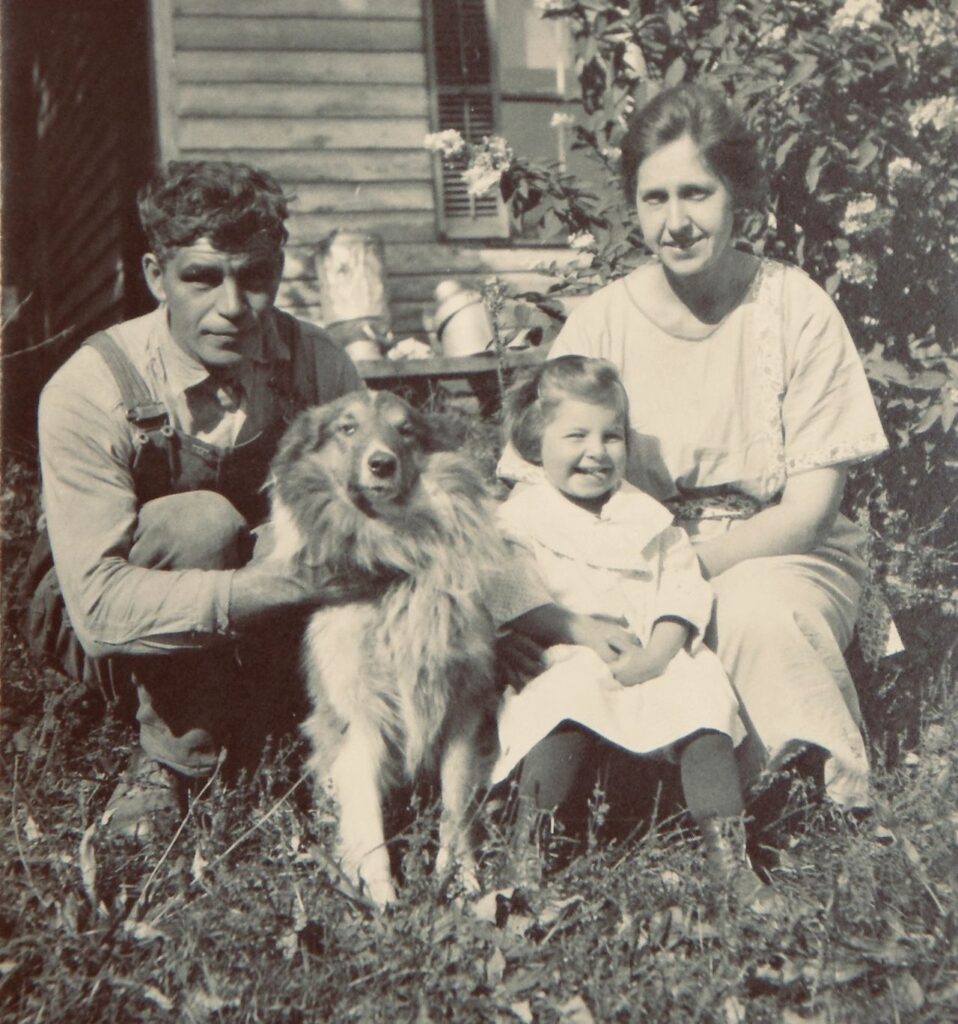

For more than forty years, my grandfather Jesse Bowman ran a little gas station and general store on the corner of Route 9N and Middle Grove Road — a place that’s called Splinterville Hill. I was raised there by my grandparents and I remember sitting in one of the blue-painted chairs that were always set up in front of that store in the warmer months of the year or placed inside near the stove when the weather got too cold, listening to my grandfather and other men talk about things. The talk was of the woods and of horses, of people they knew and things they’d done.

I always wished that I remembered more of that talking when my grandfather finally passed away at the age of 84. I still lived in my grandparents house next to that store, but I’d spent most of those first years when I’d become serious about writing away from that place and my grandfather, first in college and then teaching in Africa. When my wife and I returned to Greenfield Center in 1969, we were only to have a few more months with my grandfather before he died. Not enough to even begin to hear the stories, nor enough to convince him to tell the tales he was hesitant to speak, the ones about his Native ancestry which he tried to keep hidden. Things had been tough for Native folks around here and I heard bits and pieces of how people had been mistreated or even murdered because of their Indian blood. The body of Sabael Benedict* was never found – a visibly Native resident living just north of us on Indian Lake in the Adirondacks in 1855. It was safer to say, as my grandfather always did, “I’m French!”

I thought that those stories of the Indigenous heritage of our area were ones I never would hear, but I was wrong. In 1987, I received a letter from a man in Delaware named Don Bowman. He’d seen a piece about me in a newspaper and was writing to renew his acquaintance with me, assuming I was the grandson of the Jesse Bowman he’d known three decades earlier when he’d lived hereabouts. It turned out that, though not related to my grandfather, Don had been one of those men who came regularly to my grandfather’s store and often shared stories sitting in one of those old chairs. Don wanted to let me know he shared my interest in traditional stories and began to prove it. Every letter he sent was filled with stories of the old days. At first they were mostly about Greenfield, but then he mentioned he’d worked in the clearing of trees and buildings when the Great Sacandaga Lake was made, less than 20 miles from my grandfather’s store. My grandfather and other older men I knew had worked there, too, so I asked Don if he could tell me more about the Sacandaga. It was like asking a rabbit if he could run. Before long, I had over fifty Sacandaga stories. One or two were about the Indians of the valley and when I asked for more, Don was not long in obliging. His clearing work at Sacandaga had included the shanties, lodges and houses of several communities of “Indians” — mostly of mixed Iroquoian (Mohawk, Onieda) and Algonquian (Mahican, Abenaki) ancestry. Don had a rare gift of memory and an even rarer gift of storytelling to bring to life those people and that culture he had helped (with sorrow in his heart) to dislocate. This is not only an elegy for a way and a place that have gone, but also a reminder to us all that Native roots run deep. The descendants of those Native people of Sacandaga, though removed from their lovely valley, are not gone. They keep a low profile, but they are still here. Greenfield, Corinth, Saratoga, and the high country around the Sacandaga valley, all have their small communities of people who know their Native ancestry and hold it with quiet pride, even though things have changed, as they always do.

Presence of Indigenous Communities: Labor, Trade, and Cultural Enclaves in the Adirondack Foothills

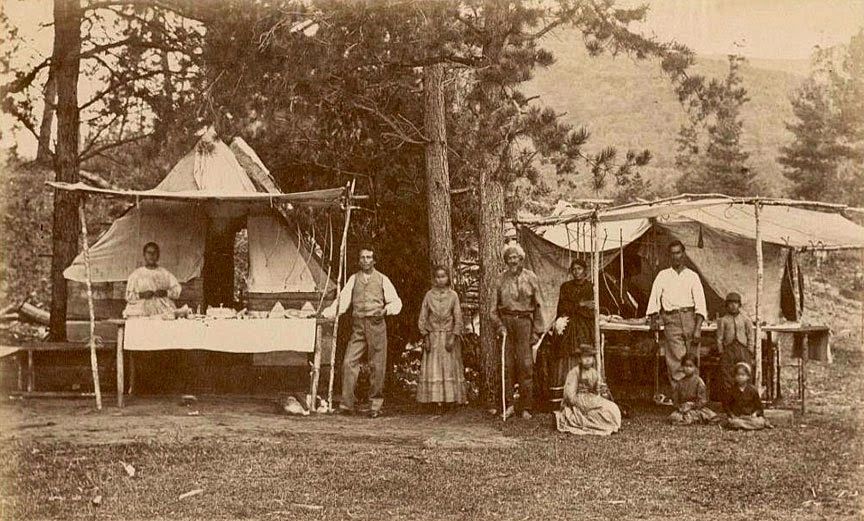

Native people, often referred to as gypsies, found employment in a variety of industries, including paper mills, glove factories, tanneries, saw mills within different settlements, forestry, and road construction. Don vividly recalled their penchant for sharing stories at local crossroads stores, like Bowman’s Store. They predominantly lived in isolated communities throughout the region. Notably, members of the Fox Hill Indian settlement in the northwest part of Greenfield, were recorded as working in the White Oak Barrel Factory, and trading goods in both Batchlerville and Middle Grove. Don told me that they affectionately called my grampa Jesse “Owl Man” and would bring geese they’d shot to his store where he’d sell those birds and give them all the money. The Fox Hill Indians also undertook trips to Saratoga Springs, where they supplied provisions to large hotels, traded furs and wild medicinal plants, and offered handmade items to tourists, such as baskets, snowshoes, moccasins, gloves, mittens, and small novelty birch bark canoes.

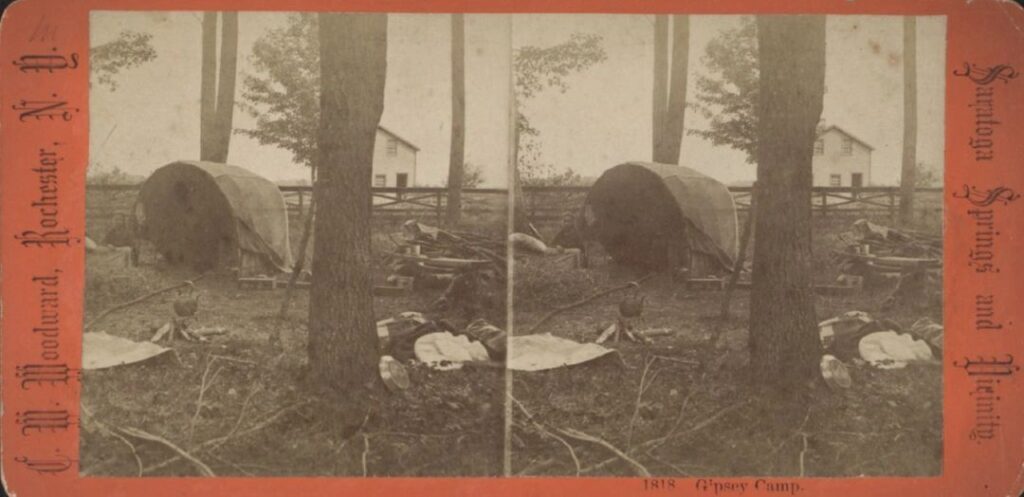

Within Saratoga and Lake George, some were also descendants of the Saint Francis Abenaki tribe. While they displayed a greater degree of openness (being seen as nonthreatening exotic visitors from Canada, soon to head back north to their “permanent” homes, afforded them this luxury). In Lake George they sometimes even sent their children to local schools, and were buried in the Catholic Church cemetery — yet, when in the region, they still primarily remained within the safety of local Native encampments. Others did chose to establish more permanent residences in Canada, but even they on occasion returned to parts of their ancestral lands in the Adirondack foothills, often for seasonal work. Native people also operated stalls at nearby fairs and journeyed to neighboring resorts.

Author of Abenaki Indian Legends, Grammar and Place Names (1884), and former Chief, Henry Lorne Masta of Saint Francis married Caroline Tahamont. Her family was from the communities of Saint Francis, the Adirondacks, and Saratoga Springs, where she and other relatives lived each summer to sell their baskets in Congress Park. Andrew Joseph, a celebrated black ash basket maker of Abenaki heritage, was born in a Saratoga Springs Indian Encampment. His father was known to annually sell baskets to the prominent hotels located on Long Lake and Blue Mountain Lake in the Adirondacks. The Indian Camp in Saratoga Springs also enticed tourists with additional attractions, such as impressive bow-shooting demonstrations.

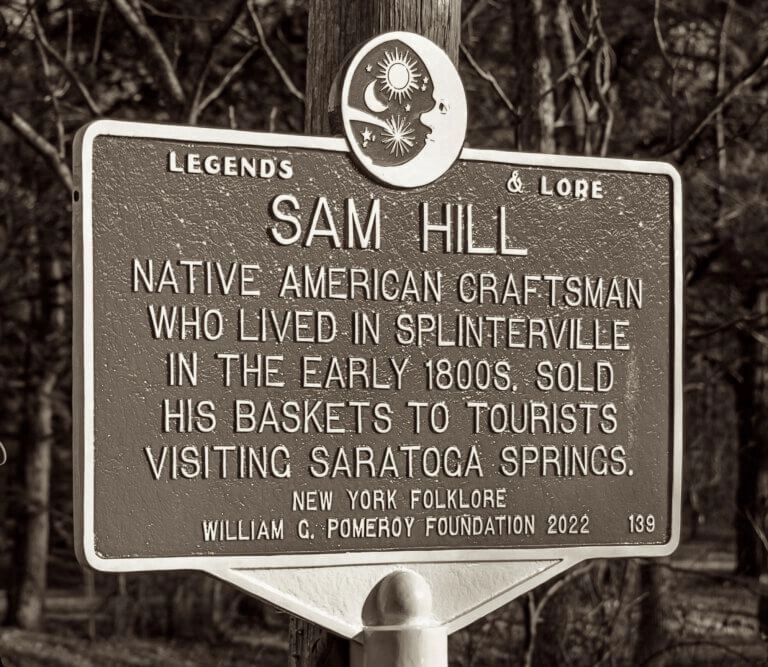

Commemorating Sam Hill: A Marker in Splinterville and the Enigma of ‘What in Sam Hill?

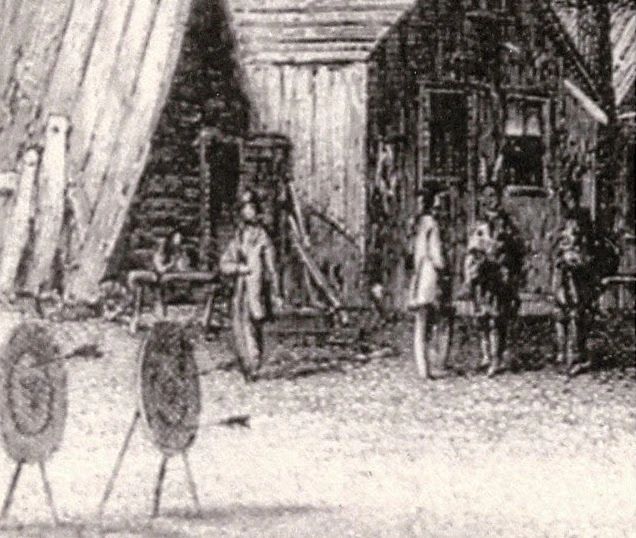

Little is known about Sam Hill* – believed to be of mixed Abenaki and Mohawk ancestry. He resided in Splinterville, near the present-day intersection of Route 9N and Middle Grove Road. The name “Splinterville” came into usage in part due to the planks laid down crosswise on the intersection – where teams of horses would turn on their way to and from glass factory mountain just north of Middle Grove (that factory was where the bottles were made that most of Saratoga’s mineral water was put into). The hooves of the horses would chop up that wooden road something fierce, throwing up a lot of splinters there. The second reason for the name was on account of splints made at the splint factories there on Bell Brook used in basket-making. Sam would often trek to Broadway, carrying a bundle of his handmade goods to sell to the summer tourists frequenting the mineral springs.

Although this tale has been passed down through generations of Saratogians, there’s limited primary source documentation about Sam Hill himself. The 1820 Census recorded a Samuel Hill in Greenfield, and in 1830, one in Saratoga Springs. While specific ages weren’t detailed in these early censuses, there is a mention of a free white male aged between 60-69 in 1830, which could potentially refer to the Sam Hill in the portrait. In the diary of Daniel Benedict from Saratoga Springs, there’s a mention of Mr. Sam Hill’s passing on July 2, 1835, described as “at an advanced age.”

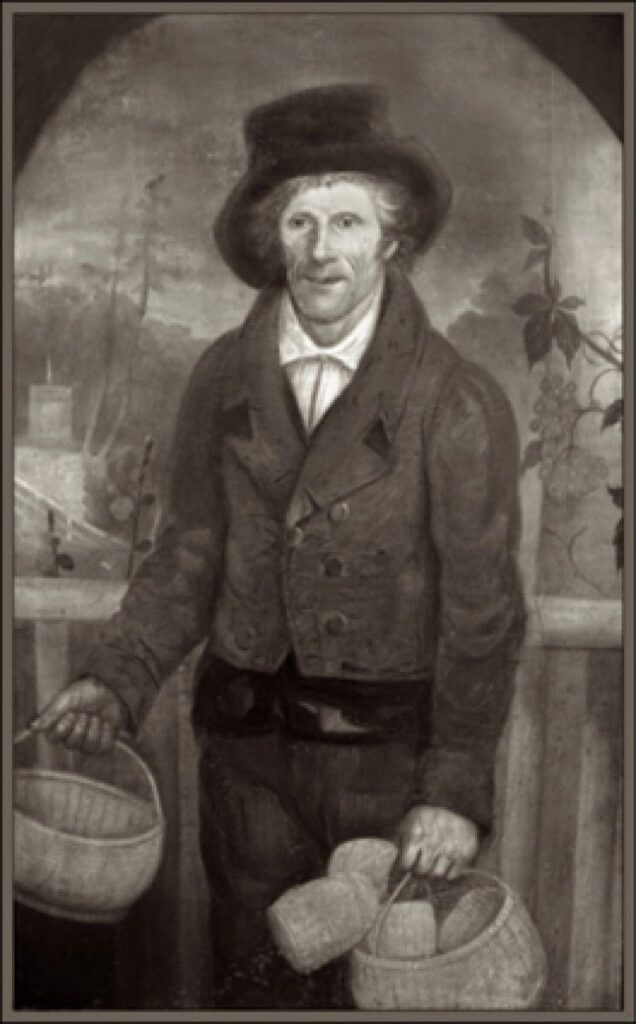

The Saratoga County Historian’s Office received a grant from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation to erect a marker in Splinterville, commemorating Sam Hill as a Native American craftsman in the community. This marker was installed in November 2022 and is situated at the intersection of Mill Road and Middle Grove Road in the Town of Greenfield, not far from where the splint factories utilized Bell Brook’s water to power their machinery. While researching Sam Hill, no information regarding him being the originator of the phrase “What in Sam Hill?” can be found. Nevertheless, his circa 1832 portrait (above) serves as a meaningful testament to his contribution and perhaps on account of him often being seen burdened by baskets he was carrying to Congress Park to sell, some attribute the proverb “What in Sam Hill?!” to Sam Hill himself.

Bowman’s Store (home of the Greenfield Review Press) sits on Splinterville hill. This new sign is located just a hundred feet up the road, across from the forever wild Ndakinna Nature Preserve.

The Legacy of Powwow Medicine: The Preservation of Native Healing Traditions in the Foothills of the Adirondacks

Folk medicine is no longer as common these days as it was when I was a child, when it was more the rule than the exception for poor folks in the foothills of the Adirondacks to go to a pow wow when they needed healing. Today, “pow wow” usually refers to a gathering of Native people, where dancing, drumming and the sale of arts and crafts occur, but the roots of the word are from the Algonquian languages of the region, where a bawwaw or bolwat simply meant someone who was a healer, one who used herbal medicines, ceremonies, and special powers to cure those who were sick and to help their community in times of special need. The word pow wow was quickly adopted by Europeans who had “powwow doctors” of their own as early as the 1700’s, using a blend of Native and European herbal medicines and “magical formulas.” Don Bowman presents some of the truest pictures I’ve been given of the ways Native communities in this immediate area made use of the old powwow traditions, at least up into the 1930’s.

The traditional stories of the Adirondack foothills contained within Go Seek The Pow Wow on the Mountain gave me back some of the heritage my grandfather’s protective silence had denied me for many years. May its gentle magic remind others of the long and lasting tenure of Native people in this land and may it be a gift for you as it was for me.

____________________________________

Parts of this post first appeared in Don Bowman’s book Go Seek the Powwow on the Mountain and Other Indian Stories of the Sacandaga Valley, Vaughn Ward, ed. (Greenfield Center, NY: Bowman Books, Greenfield Review Press 1993).

Additional information drawn from: Mohawks, Abenakis and the Indian Encampments at Saratoga Springs & Lake George, NY

*Francois Sabael Xavier Antoine Benedict TPO (1754 – abt. 1855)

*Sam Hill: Folklore & History Of A Saratoga Resident

___________________________________

For more daily bog posts by Joseph Bruchac visit his blog GENERATIONS