by Joseph Bruchac

The following blog post was written by my father Joseph Bruchac and posted here with permission from his new blog GENERATIONS.

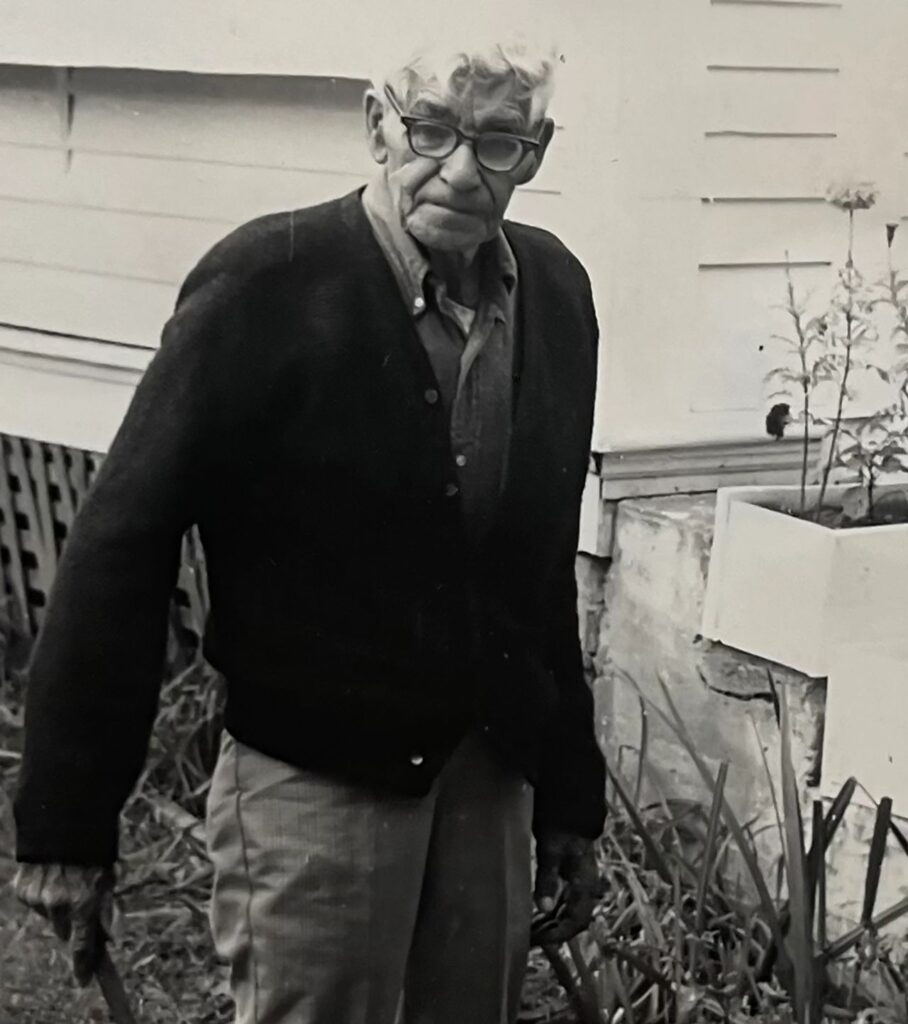

My grandfather didn’t speak about our Indian ancestry. But, there was one place where he always talked about Indians. That one place was in his garden. As I have mentioned in previous blog posts, he and my grandmother ran their little gas station and general store on the corner of Middle Grove Road and State Route 9N. In addition to running the gas station and store, Grampa was always doing other work. He worked on the road crews, especially in the winter when he drove a snow-plow.

He’d done that since the days when the plows were pulled by horses, and there were times when he would whisper “Gee” and “Haw” as he drove one of those big vehicles, smiling to himself as he felt the truck answer his commands to turn, just as teams of horses had done three decades before. No one, I was told, could handle a team of horses better than him. When someone had their team balk at going up steep Widow Smith Hill on Middle Grove Road a quarter mile from our corner, they’d come and ask my grandfather for help.

He worked, too, at what was known as the Butter Plant, right next door to the now famous Stewart’s Manufacturing and Distribution Plant just down the hill from my grandparents’ store. His job was to shovel the coal into the boilers.

Thinking of Stewart’s Shops, which was already a growing business in the late fifties when I was in high school, he’d often say, “I knew them Dakes back when they all ate out of the same pot.” I don’t think he meant that in a negative way. After all, the Dakes were civic minded and supported such things as the Boy Scouts – and have, in recent decades, acted as frequent supporters of our family run Ndakinna Education Center and Saratoga Native American Festival.

It was a reference to the way food was served back in the old days inside a long house, in a common pot kept cooking all day, where everyone and anyone could dip in for food. The Dakes, he also told me, “They had Indian blood.” Percy Dake, in fact, was a great friend of my grandfather’s and had an amazing collection of arrowheads, stone axes, clay pipes and all sort of buried objects found by amateur archaeologists at places such as the old encampment on Fish Creek, the winding, fish-rich stream that drained Saratoga Lake into the Hudson.

That friendship with Percy and the Dakes actually got me my first taste of soft ice cream before there was such a thing as Dairy Queen. I’ll never forget Grampa Jesse taking me on a private tour of the ice cream factory, at the end of which I was served a cup full of not yet frozen ice cream, straight out of the machine.

Thinking of that job of his stoking the boilers, he always had a strong relationship with fire. I have so many memories of him around the wood stove in our kitchen, where our lives centered in the cold seasons. My grandfather and I kept the wood box, with its hinged lid, filled with split ash and maple. Since my grandmother cooked on that stove, it was warm most of the day; and as soon as the leaves began to turn colors, it was kept going day and night.

Each spring he would burn the grass in the field — the way his father Louis Bowman had taught him to do it. It was an old, old way of clearing the way for new green growth, burning back the dry tangles of berry bushes at the edge of the field so that fresh, strong canes would rise up to be covered with black caps in late summer. The town of Burnt Hills to the south of us was named for the way the first settlers from Europe noted how those hills were blackened from the burning done by Native people who were still a major part of the region’s ecological balance. It was a practice even into the 1950s that was kept alive by people like my grandfather. But, after that burning was prohibited, in the years that followed the wild blackberries and raspberries that had been so common mostly disappeared.

In fact, as Charles Mann explains it in his book 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created, the first European settlers of the east coast remarked on how much burning was done, how at certain times of year the air was filled with smoke. All over the continent, controlled burning maintained such ecosystems as the great prairies and prevented the kind of disastrous forest fires we now see every year. In fact, Mann points out, when Indigenous people were pushed off their lands and those burning practices ended, it changed the atmosphere of the whole western hemisphere and may have been a leading cause of what was known as the Little Ice Age—the period of disastrous regional cooling that lasted until the mid-19th century.

As my grandfather burned the fields, I followed behind him with a rake, moving the burning grass back onto itself, helping him make a flaming circle that would feed on itself, growing smaller and smaller until all that remained were a few embers at the blackened heart of the field. Our feet would be black with the soot of burned grass.

There were times, though, when the wind would turn. Then the fire might run ahead of us in directions that we did not expect. With the rakes and shovels in our hands we would beat the burning grass, making sparks fly up so high that I was certain they became stars.

Finally, my grandfather would stop and lean on his rake. “Guess the fire department’ll get here soon,” he would say. And we would listen for the familiar sound of their siren, coming down from Greenfield after the fire spotter in his tower on Spruce Mountain, eight miles to our north, had taken note of the rising smoke and called it in to them.

I’d soon see the red truck of the Greenfield Volunteer Fire Department. It was exciting because I knew, even as a small boy, that open burning like this was illegal without a permit. But when the fire dept. would arrive, big smiling men would climb off the pumper truck and begin to wet down the edges of the fire. “Jess, you old firebug!” one of them might yell. My grandfather would not answer. Sometimes, though, he might lean over to me and say in a soft voice, “This here is one way to keep them firemen in business.” I would nod, understanding his words.

I remember those fires every spring, so too I remember my grandfather’s garden. Another of my earliest memories is walking through his garden – Grampa seemed taller than the biggest trees then — holding his hand. I could barely walk, even on level ground, but he wouldn’t let me fall. I wore the same kind of overalls that he did, and people were already calling me “Jess’s Shadow.”

That was how Lawrence Older put it one day when he was buying gasoline at my grandparents’ filling station. I was following behind my grandfather, my tiny hand holding onto his overalls because his hands were too busy to hold mine. “Jess,” Larry said, with a twinkle in his eye, “that grandson of yours stays so close to you he don’t hardly leave room enough for your shadow.” Jess’s Shadow? I didn’t quite understand that name. My name was Sonny. I knew that for sure. That was the name my grandparents called me by. I never heard either of them speak to me or about me by any other name.

I remember the day I could not have been more than two and a half years old — when my grandfather said to me, “Sonny, cup out yer hands.” I held them out together, trying to make a really good cup. Carefully, taking the seeds out from the cloth sack he had slung over his shoulder, he filled my hands with kernels of golden corn. I stood there holding those seeds for him, watching as he took them, four at a time, to plant them. “Yer turn now,” he said when those seeds were gone, and he held out one leathery hand filled with corn. I’d watched really carefully, so I knew what to do. I did it so well that my grandfather said, “yer already better than me, Sonny!” Then, as I planted my first hills of corn, he talked to me about things.

He always talked more when he was in his garden. There in his garden, as he spaded or began to hoe, he would talk about the different plants, about the birds we heard singing, about how we had to watch for the woodchucks or the rabbits or the raccoons. Sometimes he would talk about the old way of plowing with a team of horses, and he would tell me the names of the horses he’d loved – the last of them dead and gone a decade before I was born. He told me how he and his father used to turn up arrowheads as they plowed the fields. “Indian arrowheads,” he would say.

He had a name for that work of preparing his garden for the sweet corn and green beans and butternut squash we always put in. “Fitting the ground to plant.” That is what Grampa called it — according to his younger brother Jack, who I met much later in life, that’s what their father, Louis Bowman, had called it too.

One spring day, when I was about 5 or 6 years old, I was working with my grandfather in the garden when all of a sudden, he stopped hoeing. I stopped too and waited. I remember that I heard a bird sing just then, a long ululating song. “Oriole,” my grandfather said. Then he bent over and picked something up. He brushed soil from it and went down on one knee next to me. “Sonny,” he said, “looky here.” I leaned close to look at the dark, blocky piece of flint that filled my grandfather’s broad hand. “Indian,” my grandfather said. “Ax-head.” He hefted it first in one hand and then the other. He did it with the same care that my grandmother used when she was gathering eggs in the hen house and putting them into the basket hung over her arm. Then he placed that ax-head into my hands.

______________________

Indigenous peoples of the northeastern woodlands traditionally used fire as a technique for forest management, periodically burning the understory to clear away dry brush and leaves, encourage new growth, attract game, improve visibility, and keep trails clear for easy travel. For more information, see:

Gordon M. Day. “The Indian as an Ecological Factor in the Northeastern Forest.” Ecology, Vol. 34, No. 2 (April 1953): 329-346.

This story is drawn in part from Bowman’s Store: A Journey to Myself (1997)

______________________

To read more daily blog posts from Joseph Bruchac check out his blog GENERATIONS.