To read more of my father’s daily blogs, check out GENERATIONS

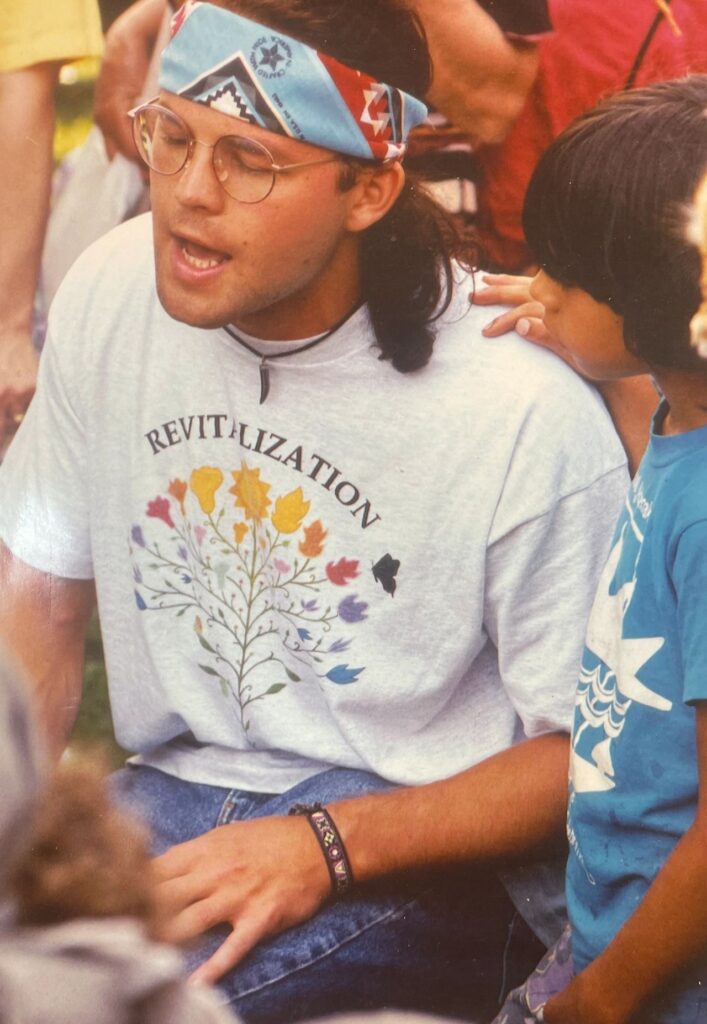

In 1992, my son Jesse began playing on two traditional-style Abenaki drums: The Missisquoi Drum in Swanton, VT, and Awasos Sigwan (Bear Spring) Drum in Odanak, PQ. Both drums had recently formed and had a limited number of songs. Members of both groups were gathering songs from their families and playing popular songs from Eastern Eagle and the exceptionally powerful Mi’kmaq musician George Paul originals.

During that time, Jesse was also taking language classes from Abenaki language teacher Cecile Wawanolet. Inspired by these classes and the original songs of George Paul, he began composing traditional-style drum songs. He used his knowledge of the Abenaki language, which Cecile had shared with him and others in both Abenaki communities. She held classes in her home reserve community of Odanak, PQ, as well as in Missisquoi, VT.

Songs Remind Us, When We Forget

Listening to a recording of them singing, with strong voices, I find myself recalling things I had forgotten I knew. That’s the magic of music, with the sound of those old words, the rattle and the drum resonating with your heart and your breath, resembling the thunder and the wind. The songs they sing on that recording include ones that Jesse composed in Abenaki.

When I hear one of these Abenaki songs, composed by my son Jesse, I can’t help but think of my grandfather Jesse. I look at the playlist and see the name of that old, new song my son has written: “Fishing Song.”

I remember the first fish I caught. My grandfather drove us up Ballou Road, past the cemetery where his father and mother were buried. There, just below the hill where stood the house in which he’d been born, the South Branch ran under the road.

I could hear the gurgling voice of its water on the rocks as it came out of the throat of the stone culvert under the bridge. He handed me his old bamboo rod, a worm already placed on the hook. He knew I was big enough to catch a fish all by myself, even though I was only six.

“Jes’ walk up slow, and don’t look over into the water, or the trout’ll see you. Jes’ whisper what I tole you and drop yer line in the water.”

I did as he said. I crept quietly, as quietly as I possibly could. Inch by inch I stuck the pole out over the wooden rail. Then I whispered, “This is for you,” and flipped the line into the water. The trout struck it as soon as it hit the surface, yanking my line. I pulled back and the trout came spiraling out of the water to land on the bridge. It was a ten-inch-long brook trout, and it seemed as if all of the colors of the rainbow were there in the spots on its sides.

My grandfather picked it up and carefully wiped off the gravel from the road that had stuck to its sides. He said something that I couldn’t hear, and then, putting his thumb in its mouth and his index finger on the top of its head, he gave a little twist. A quiver ran down the body of the fish and it was still. He took the hook out and placed the trout in my hands.

That was the only trout we caught that day. We didn’t try to catch any more fish. That one was enough. My grandmother cooked it for my supper that evening.

Songs remember, and my son Jesse continues to write songs in the language. I shared another new one of his in my New Year’s blog post, Greeting Maker. Some of those early songs he created for the drum groups in 1992 are now heard throughout New England, sung on a number of Eastern woodland-style drums. These are often considered old songs by those singing them.

Thanks to Cecile’s teachings and the songs’ power to aid in memory, Jesse has become a teacher and a fluent speaker of western Abenaki. And it is no surprise that he uses songs as a “primary driver of language reclamation.” If you’re interested in learning to speak and sing the western Abenaki language, be sure to check out the Middlebury School of Abenaki.