The following blog post was written by my father Joseph Bruchac and posted here with permission from his new blog GENERATIONS.

Just below my grandparents’ house on Splinterville Hill is a small stretch of woods. No more than fifty yards deep, it ends at the stone wall that marks the edge of our property line, as stone walls now do throughout the Northeast. Following the line of the stone wall, the woods stretch from Route 9N on the east to Mill Road on the west, where they are bordered by Bell Brook.

There I first followed the tracks of animals in the snow the exclamation-mark paw prints of rabbits, the round, delicate tracks of red fox, the tiny marks of field mice that would end at a circle in the snow where their hidden runs dove out of sight. Although it seems small today, that little forest seemed very large to me when I was young. I always called it the woods; and when I went outside after school or on the weekends or in the long summer days, I only had to say to my grandparents, “I’m going to the Woods,” and they’d know where to find me.

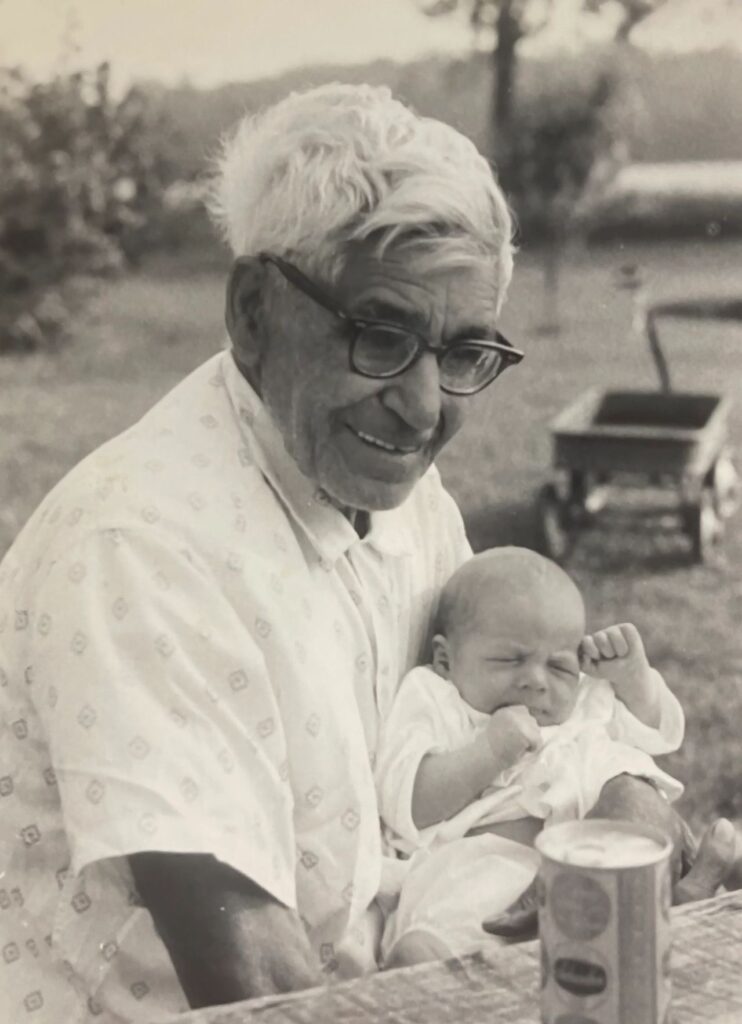

It was my grandfather who first walked with me in the Woods, holding my tiny hand and reassuring me that this was a place where I could be safe as long as I understood what was around me. It was not that I couldn’t get hurt there. You could get hurt anywhere, Grampa said–and I surely understood that. But knowing what could hurt you, that could help you keep away from it. He showed me the nettles that would sting my skin, and the thorns on the raspberry bushes. He pointed out the places where the wire of the old fences that had been buried over the decades stuck up and might trip me. We were always pulling out those old wire-mesh fences.

For everything in the woods that might harm me, my grandfather pointed out a dozen things that gave me delight. He showed me the different kinds of trees, from the smooth-branched maples to the rough-barked elms. He showed me the three big old apples, ancient gnarled trees that were covered with sweet-scented flowers each spring. Although the fruit that came on them each late summer was small and marked by insects, no apples in the world ever tasted as good as theirs, and my grandfather said we’d maybe build a tree house in the biggest apple tree one day when I was big enough.

He showed me how I could swing on the grapevines and how I could make places to hide under the honeysuckle bushes, just like a rabbit does. He showed me the different rocks, how some of them were soft sandstone that you could break pieces off with your hand, while others were hard and had quartz in them that sparkled brighter than diamonds. He showed me how some rocks were alive once. “Though maybe they still is alive, in a way of saying,” he added. They had fossils in them, like the ancient blue cryptozoan stones that made up the stone retaining wall right behind our house, a wall my grandfather had built. More than anything else, though, I remember how he showed me the flowers. And more than any other flower, I remember the first one of them all, the bloodroot.

It was in the Woods that I first saw bloodroot in bloom, that delicate white flower which is the first spring blossom in our Adirondack foothills. Rising up on a smooth stalk, its center is as golden as a tiny sun, surrounded by white rays of light.

“Soon as you see the bloodroot,” my grandfather said, “you know winter is goin’ fer sure.”

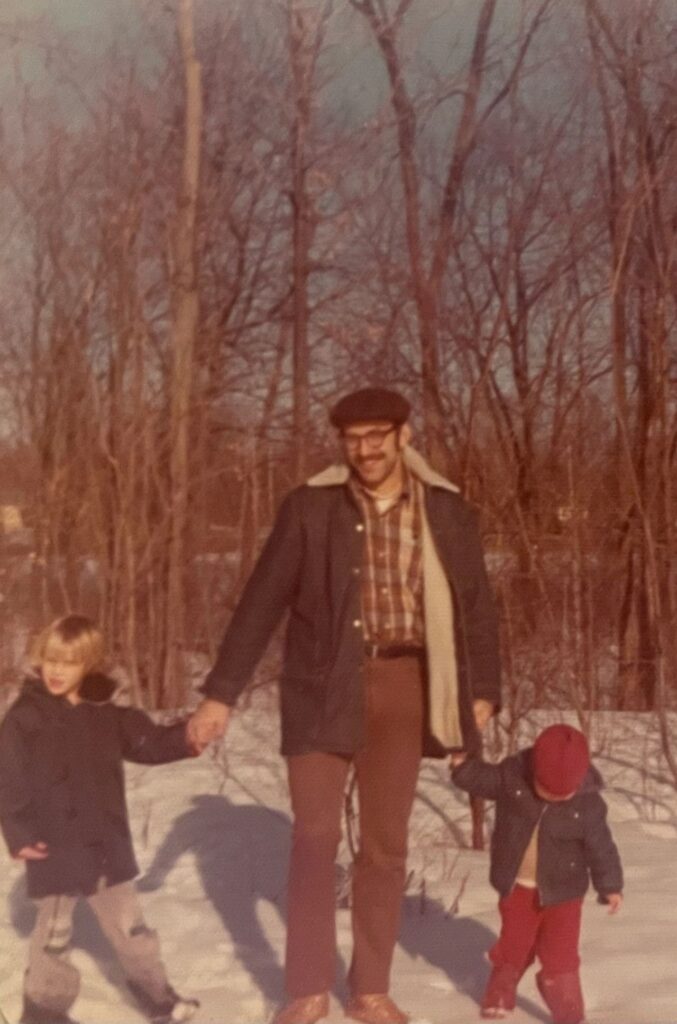

When the last mounds of April snow were shrinking down in the huge dirty piles that the town crews had plowed up below our driveway, Grampa and I would put on our green rubber boots. Mine were exactly the same as his, but so much smaller that I could put on my boots and then pull his on over mine. Then I would go galumphing along next to him, giggling while he said to my grandmother, “Wull, Sonny’s got his boots on, but now I can’t find mine.” “Grampa!” I would finally say. “Look! I got your boots on.” He was always surprised at how silly he had been, not to be able to see that. Then we would go down into the Woods to look for the bloodroots.

There would still be little patches of snow here and there at the bases of trees, and the ground was alternately hard as rock or so soft that our feet would sink in, and we could only pull them out with a sucking sound, as if the earth wanted to swallow us. Soon, though, we’d find the first patch of bloodroot. They would be clustered together in a circle, the green palmate leaves surrounding the base of the white flowers that thrust up toward the sun. My grandfather would always pick one of those first bloodroot flowers we saw. Then he would take its stem, which dripped orange sap like ink from a broken pen, and make marks on my face as I looked up at him.

“This here’s yer spring paint,” he said. “Helps keep them bugs away.” The lines and circles he painted on my forehead and cheeks would dry there, and I would forget that I had them–until I looked in the mirror later in the day, or saw how a customer stared at my face as I stood on an empty Coca-Cola box to clean the windshield while Grampa pumped the gas.

Sanguinaria canadensis is the Latin name for the bloodroot. I looked it up when I was eight years old and wrote it down in one of the notebooks I kept then, listing every bird or flower or animal I had seen. I learned, as I read my field guides, that it is a member of the poppy family. Found in the humus-rich woodlands and along streams, its range is across Canada and south from Nova Scotia to New England. Fragile and brief as the first days of spring when it blooms, its flowers open to the sun and close at night-like small white hands, trying to hold in that first warmth. Its Latin name, sanguinaria, means “bleeding.” The orange juice that comes from its stems was used by the Wôbanakiak/Abenaki and the Kanien’kehá/Mohawk people as an insect repellent, as a dye for clothing and baskets, and as an ingredient in face paint.

And so, once again, without saying or perhaps even knowing, my grandfather handed down to me a part of my heritage that was as ancient as the story of the coming of spring.

To read more of my father’s daily blogs, check out GENERATIONS

_________________________

A version of this story appears in Bowman’s Store: A Journey to Myself, Joseph Bruchac (1997)