It’s been more than 50 years since I took my first martial arts class. After seeing a flyer posted on some anonymous wall, I went to the high school in Ballston Spa, where my first teacher offered instruction in the martial art of Indonesia, Pentjak. Although his given name was Dutch, he went by various titles in Bahasa Indonesia, the native language of that vast archipelago he and his family had escaped from during the purges of “Communists” and people of Eurasian ancestry by the Sukarno government in the 1960s. Guru, Mata Elang, Gison Tenaga.

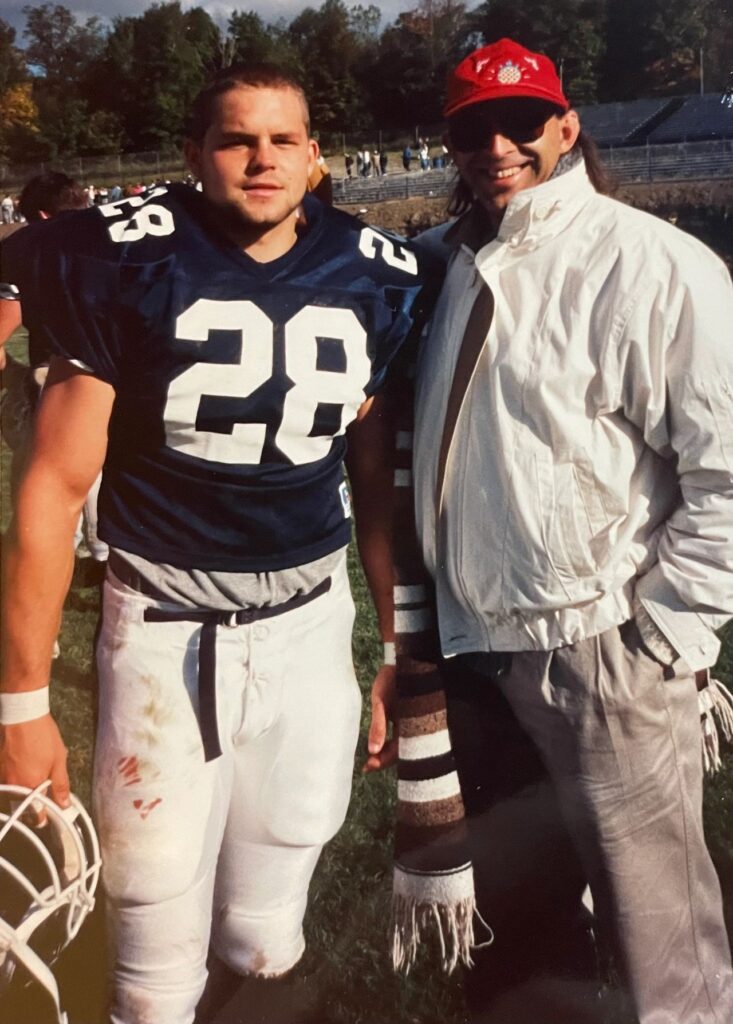

I studied with him for over a decade, gained my black belt, and eventually became his head instructor. When my own schedule and my commitment to the athletic careers of my two sons (in wrestling, where I worked as an assistant coach, and in football, where I became the head of the Saratoga High School booster club and then began making trips with my wife Carol back-and-forth to Ithaca college where both Jim and Jesse played on teams that won two national championships) made it impossible for me to continue teaching Pentjak, I never stayed far away from martial arts, doing workshops over the years that followed in many different disciplines, including Capoeira, Tai Chi, before eventually coming back to Pentjak when — two decades ago, I joined the Pentjak Karate school, headed by Jim Devoe, who had been one of my students in the 70s and advanced to Master’s Rank with a 5th-degree black belt. In the meantime, my son, Jim, earned his own 5th-degree black belt in Kyokushin: Full Contact Karate.

Then came BJJ. My younger son, Jesse, then living near Buffalo, started his own mixed martial arts academy with Brazilian jiu-jitsu at the center of it. That gym called WNYMMA produced some major talent in MMA; including Paul Bradley, and UFC Heavyweight Champion Jon Jones (Jesse and I are in the back row of the photo in their cage, taken during one of my many visits). When I visited, I started classes in BJJ, which complemented my college wrestling beautifully (at its core, BJJ is the art of wrestling with the addition of what would be deadly and bone-breaking submission holds were it not for the ability to tap out). His brother, Jim, became involved when Jesse moved back home to Greenfield Center. He sold the gym in Buffalo, which is still thriving today. Eventually, all three of us were teaching BJJ together. We are still doing so today in our own Alliance Jiu-Jitsu Saratoga dojo at the Ndakinna Education Center, where we are three of our eight black belts — and where we also helped propel UFC contender Mike Davis to his current meteoric rise.

All that by way of a prelude to a few stories I’d like to share that relate to the title of this essay. Fighting without fighting.

If you are a fan of Bruce Lee, as I was and still am, you’ll probably recognize that phrase from a scene in his biggest movie, ENTER THE DRAGON. While on a ship loaded with martial artists on their way to a tournament on a mysterious island, Lee is confronted by another fighter who wants to challenge him. When the guy asks his style, Lee answers, “Fighting without fighting.”

When I first saw that movie, I didn’t realize how much that phrase came from ancient Chinese culture. For example, it relates to Lao-Tzu’s Dàodé jīng, from which Lee’s famous instruction to “be like water” stems. It also echoes the philosophy of Sun Tzu’s classic book, THE ART OF WAR, in which direct confrontation with the enemy is the least desirable path toward victory.

One more thing I’d like to add as a prelude to these stories of mine is that my decades of study have taught me several techniques that, if employed correctly, could gravely injure or kill an opponent, but the more of them you know, the less you need to use them.

My first story comes from a night about 40 years ago when I returned from doing a poetry reading at the Nuyorican Cafe in New York City. I was at the Port Authority Bus Terminal in a very sketchy part of the city. My bus had been delayed, and it was past midnight. I was sitting and reading a book in an area of the terminal that was almost totally deserted. Then, a large man wearing a shabby gray coat came and sat beside me. He leaned close and said in a threatening voice, “I have a knife.”

I didn’t turn to look at him. I said, “How nice for you.” I kept reading. I looked up from my book a few pages later, and he was gone.

My second story is from a few years ago. We celebrated my stepson Mikael‘s birthday at one of our favorite restaurants. We were in the room where the bar was behind me and close to our table. The room was crowded with a group of people who, I later learned, were coming from a funeral.

Suddenly, one of the voices from behind me got louder and angrier. A sizable young man, probably in his mid-20s, began making threatening remarks, well mixed with profanity, toward other older men in that group. The bartender said something, trying to calm the situation down. That was when the young man threatened to kick the bartender’s butt and knocked over one of the tall tables with a loud crash.

I stood up, took one step, and put my arm around the angry young man’s shoulders “You don’t want to do this,” I said. “Let’s walk outside.” I don’t recall exactly what I said as we went out the door of the restaurant together, but he wasn’t resisting me. When we reached the sidewalk, I told him he better go because they’d called the police.

Then, without a word, he went. When the police arrived a few minutes later, I was back at the table, enjoying Mikael‘s birthday party. Could it have happened that way without my decades of training that taught me to be calm and trust what I had learned from so many teachers? I don’t know. But one thing that I do know for sure is that those were two of the best fights I ever had — without fighting.

1979 Pentjak Class. Joseph Bruchac is in the back row, his two sons, James and Jesse are seated in the front row.